Author: Paula Gooder, 10 March 2017

Thought the wilderness was just a place of desolation? Think again. Paula Gooder reflects on the ‘great and terrible’ nature of the wilderness – and her first trip to a desert.

I will never forget my first experience of wilderness. I was on a visit to the Holy Land and went out to the desert near the Dead Sea. I fell asleep in the bus on the outskirts of Jerusalem and woke, bleary-eyed, to find myself in what felt like a different world. It was the middle of summer and the sun’s rays beat down on an already scorched landscape.

The air above the sand shimmered in the heat. Sand stretched as far as the eye could see, broken only by the odd scrubby plant that rose dusty yet defiant from the arid earth. That first experience of the desert had a powerful effect on me in a number of ways, but what struck me most about the territory was its ambiguity: it was at the same time alien and familiar; forbidding and inviting; lifeless and life-giving.

We didn’t stay for long. We were on a tight timetable. But the wilderness remained with me long after we left. Nearly 30 years later the emotional memory lingers on, especially when I read passages about it from the Bible. It is not hard to see why the wilderness occupies the place it does in the popular imagination of the biblical writers.

The desert was where people, like Hagar and Ishmael, were cast out and abandoned (see Genesis 16.1–16); it was also the place in which they met God and were saved (see Genesis 21.17–20). It was where God’s people found refuge and protection from their Egyptian oppressors (see Exodus 16.1ff); it was also the place where they feared they would die from hunger (Exodus 16.3).

The people of God entered the promised land through the wilderness and left through it again as they went into exile hundreds of years later. The wilderness was great and terrible (Deuteronomy 1.19).

The wilderness was where God was expected to return (Isaiah 40.3). Wilderness, both as a location and as a theme, runs all the way through the Old Testament and onwards into the New Testament. Its symbolic significance is one that we will explore in different ways, through the lens of different passages as this book unfolds.

All the way through it remains a place of ambiguity, bringing both danger and salvation. Lent is a season that invites us to step into the wilderness with all its ambiguity. It challenges us to be courageous and face the vulnerabilities we might naturally shy away from. It summons us to learn lessons about ourselves: who we are and who God calls us to be. It suggests that while what we fear most might sometimes bring exactly what we expect, at other times it can bring salvation and hope.

There is no easy way through the wilderness; no shortcut route to take. Entering the wilderness takes courage and strength of heart, and we are not always able or strong enough to tackle it, but when we are able and strong enough we can find in it not bleakness but spaciousness; not terror but hope; not disaster but the very salvation we crave.

Paula Gooder is Bible Society's Theologian in Residence. This is an excerpt from her book Let Me Go There, published by Canterbury Press.

Share this:

A 100-year Bible dream comes true in China

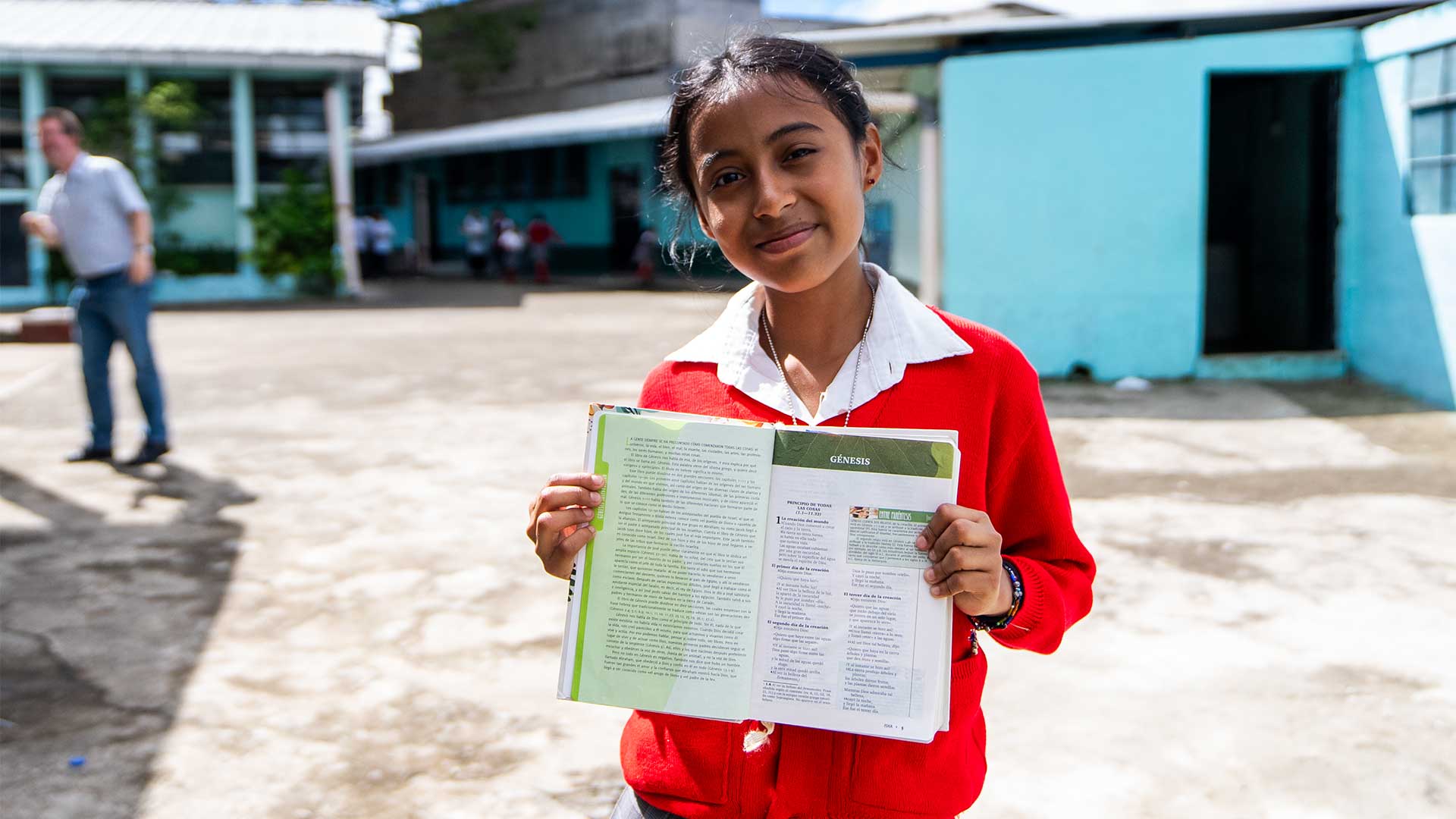

Change a child's life with the Bible