Author: Girma Mohammed, 29 April 2021

George Floyd’s death focused world attention on the consequences of racism. Girma Mohammed asks what the Church should be saying.

Police brutality on black males is a well-documented phenomenon in American culture. The killings, however brutal, are often subjects of a polarised media circus. In many cases, the establishment finds legal and political resources to justify them. And another round continues. Something was different, however, with the killing of George Floyd. Firstly, the whole process of the killing was filmed. Secondly, the calm and cold demeanour of the killer – a police officer – as he knelt down on the neck of the helpless black man was unnerving. Thirdly, the victim was begging, ‘I can’t breathe!’ – a phrase that became a rallying cry for Black Lives Matter (BLM) protestors. The combination of these three reasons elicited emotional reactions that sent a global shockwave. However, a deeper and more unsettling aspect of these routine atrocities is often forgotten in the ensuing conversations: fluctuation in the value of human life.

It was in South Africa. A man had fallen in a drainage channel on the roadside. Another man was shouting, ‘White man down! White man down!’ Note that South Africa has a very difficult racial history, and it is a country that is still haunted by its past. There is no proof to show the person calling for help was ill-intentioned. All the indications are that the caller was a product of the worldview that sees human beings through the prism of black-white binary. As a result, he went to his default position of subscribing to the politicised adjective – ‘white man’. The intuition is to generate a certain reaction in terms of the intervention by adding value to or taking it away from the person in question.

...

George Floyd’s story was no different. He is a ‘black man’ – the adjective is hard to miss. That adjective has multi-layered manifestations in real life. In the life-system of the people of African descent who live in the Western hemisphere, his killing was not a distant and theoretical ethical mishap. It was an integral part of the imminent danger they face in their day-to-day life. For them, it brings existing fear and uncertainty closer to home. This danger is captured very well in Ethio-Canadian singer and songwriter Ruth B’s song, ‘If I have a Son’. The song goes:

If I have a son, I’ll teach him to be brave

Cuz if I have a son, he’s never really safe

And when you run to the corner store for a snack

I wanna know that you’ll make it back home

For the global black community, the killing of George Floyd, and the manner in which it was executed, carries a painful symbolic significance. When George Floyd was denied his right to breathe, his plea, ‘I can’t breathe!’ reverberated all the way to Ghana, Senegal and Kenya. They experienced the emotional trigger of the colonial and imperial suffocation. It forced many to re-live their painful past.

Then there are those who are usually indifferent towards injustice to black minorities. They were caught off guard in George Floyd’s killing. He was killed on camera. The viral nature of the news means it made indifference uncomfortable. Some decided to voice their support for the protest because they were genuinely shocked and appalled by the injustice. Others offered half-hearted lip service because silence became untenable.

For others, this tragedy is a commodity. It is hard to resist the desire to use the tragedy as a vehicle to achieve their political goals. The BLM movement acquires its political relevance when it is attached to political issues. It creates a vote-winning opportunity across the political spectrum. Some would ride on the promise of mainstreaming the demands of the people group who are left in the social and economic margins. Others use it to galvanise their base on the promise of protecting them from racial and religious newcomers. They both have two things in common. Firstly, they both know there will be very little change beyond lofty rhetoric. Secondly, they all want the politically infused adjective in the spotlight – it is politically profitable.

There are a number of measures that are being taken to address the concerns raised by the BLM protesters. Under intense global pressure, government bodies, educational institutions and companies feel they have to do something. Some of these actions are very superficial, almost bordering on comical. For instance, estate agents across London are banned from saying ‘master bedroom’ so as not to offend black buyers. Instead, they are forced to call it the ‘principal’ or ‘primary’ bedroom.

The same rule applies across America in furniture and housing companies. As bizarre as it may sound, such a measure has a legitimate intuition. Part of the reason is that the primary social mechanism that guides memory is language. This is precisely because reality is mediated to us through language. However, this fact is deployed in a way that promotes superficiality in righting historic and ongoing wrongs. Furthermore, it addresses problems that are non-existent or not the primary source of injustice. For example, one has to go a long way to find, if one can at all, a black person who is traumatised by the designation of a room as a ‘master bedroom’.

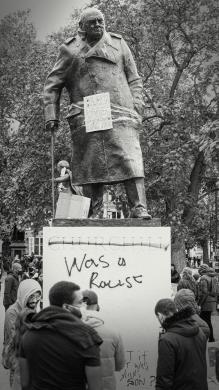

A more controversial measure was the removal or a call to remove the statues of slave masters or prominent colonial figures. This became a talking point from Cape Town to Kinshasa; from Bristol to Birmingham, Alabama; from Brussels to Beaumont, Texas; from Oxford to Indianapolis.

One important aspect of this controversy that begs a question is: What would the removal of statues accomplish in terms of alleviating the day-to-day struggle of ordinary individuals in a racially charged world?

...

Statues are not necessarily about the past. They are about securing the future through the ancestors. Therefore, in an ideal world, for the subjugated, removing the statues would bring some sense of closure for those who struggle with painful memory. Such an action would open a new, and perhaps more egalitarian and accommodative paradigm. It would give a feeling that the plights of the subjugated have been listened to and accounted for by society.

For those who are against the removal, their future is their past. The extreme elements in this camp feel their glorious past needs to be re-enacted in a certain manner. Others are more calculated. For example in Edward Colston’s case, they chose to remember Colston’s generosity to the poor in Bristol while they decided to forget the atrocities he committed against African slaves.

Therefore, removing or retaining them should have been based on consensus that comes out of compassion for those who are hurting. Such a consensus does not come as a result of a rapturous movement sweeping across the world. Instead, it takes careful education so society could identify and discern the chaff from the grain. It takes time to bring about a change that comes not come out of coercive pressure, but out of discursive conviction. Otherwise, the combination of force and pace could produce either a shortcut for cheap redemption for those who feel guilty or a backlash from those who are angered. This would, in turn, make the discursive space more hostile, and diminish the virtue of listening and learning from one another.

The duality between the right teaching – orthodoxy – and the right practice – orthopraxy – is where Christians struggle when it comes to BLM issues. After a quick run through Christian media outlets, one would realise that there is not much to fault Christian community when it comes to orthodoxy, even though it is unrealistic to expect uniformity when it comes to the details.

...

However, it is that transition from right theology to right action that has proven to be elusive. While there are churches which are intentional about bridging racial divides, there are many who still struggle to land their message of equal human value in practical life. What, therefore, are the areas of action that need to be considered?

Firstly, the Christian community – as the body of Christ – needs to reconsider the way it engages with agendas set by political entrepreneurs. Ideologues often tap into half-truths or ride on dominant feelings. The Church needs to set an agenda of its own that is biblical and inclusive to prophetically engage the public discourse. It needs to be a leader, not a follower, in matters of justice. When the Church loses its direction in dealing with injustice, it will lose its ability to speak with authority in matters such as BLM issues. Politicised racial adjectives are traps – they undermine the ability of the Church to speak the truth without fear or favour.

Secondly, there has to be a common recognition among Christians (blacks and whites) that George Floyd symbolises humanity, not only a black community. When one human being denies the right of another human being to breathe, and does it with impunity, the depth of the problem is beyond racial. The whole incident is a dramatic example of the depth of human brokenness. The discussion, therefore, should be taken beyond skin colours. Anger is the right reaction in the face of atrocity. However, it would be unfortunate if this anger were directed solely towards a few individuals – police officers in this case – or to a specific group. The Christian community should be angry at the mind-set or ideological tenets that divided humanity into hostile groups. It is very clear that black people bear the brunt of physical abuse, economic marginalisation and social injustices. However, the spiritual damage transcends racial boundaries. The response, then, should not be sheer force, but education and discipleship to make human persons whole.

Thirdly, the Church needs to take a reasonable distance from the political establishment and provide a prophetic voice on public issues such as this. As I hinted above, the Church has dropped its ball. It has lost its incarnational posture, and has left open a way for corrosive political elements to subvert its narrative. Its preoccupation with ‘culture war’ has made the Church lose an important war that the Church, from early on, was very keen to address – diversity and inclusion. The Church, therefore, cannot act as a distant commentator on this tragedy – it is an important contributor to it. Racial violence is a result of narrative tragedy. The Church, as a crucial storyteller in the culture, has failed to construct a common destiny that transcends tribal fault lines. There is a need, therefore, for the Church to take a distance from ideology and draw its message afresh from its original source – the examples of Christ.

Finally, the Church and Christian organisations need to set concrete examples of inclusivity and equality. This starts with understanding and recognising the uphill battle that young black people have to get opportunities. The window of opportunity for black people is as narrow in Christian organisations as elsewhere, if not even narrower. When they get one, those opportunities come with extra struggles in workplaces. Once a friend said, ‘Black people are greeted with suspicion in their positions until proven otherwise, while white people are greeted with trust until proven otherwise.’ Even those who are highly qualified struggle from unconscious biases as well as conscious, and subtle resistance embedded in the system. There is no ready-made answer for the challenge of unconscious bias. However, Christian organisations should be more intentional about addressing it. This could mean opening doors, entrusting them with responsibilities and mentoring them so they can thrive in them. This includes creating a level field in job opportunities, empowering individuals with talent and coaching them into leadership roles.

Violence against another human being is a dehumanising experience, not only for the victims, but also for the perpetrators. The only difference is that one bears the physical scars whereas the other faces spiritual deprivation. The Church has the mandate to address both. The activism of the Church in the public sphere – vis-à-vis BLM issues in particular – needs to address the totality of a human being. A discourse of justice that takes skin colour as a point of departure, however sophisticated it might be, is bound to fail with regards to bringing a lasting solution. It doesn’t go deep enough because it stops at the skin. That is the reason why a Christian approach to racial justice needs to make a combined effort to address the mind-set as well as performing concrete actions on the ground such as education, employment and improved workplace policies. The goal, therefore, is re-humanising – restoring the distorted divine image in humanity.

This article appears in Faith in Public Life, the new digital magazine produced by the African Biblical Leaders Initiative (ABLI).

Share this:

A 100-year Bible dream comes true in China

Change a child's life with the Bible